Fawning.

Mistaking fawning for effectiveness and culture fit.

I have spent most of my career freelancing, jumping from project to project, observing team dynamics from the top down. When you move that frequently, you see patterns that entrenched employees and managers often missed. The most glaring pattern is a disturbing reality: people who fake charisma, often go further than people with competence and clear performing metric.

Research and anecdotal evidence suggest that charisma, when perceived as authentic, can significantly influence career progression, with one study indicating that charisma accounted for team members to consider the other member who score high in charisma as more effective — (Shonk, 2025)

Personally, I learned this the hard way when I was kicked out of a team in under a month. The founder expected me to fawn; I stood on my merits instead, not knowing this will cost me the contract. “Bye,” he said. While painful, that experience crystallised a critical theory often neglected by managers. I was performing, doing my task, and I like to go extra, asking all sort of questions to unblock my team, which will be a clear indicator of someone that’s willing to do their job. These were questions others were afraid to ask, for obvious reasons. I forget that I was suppose to act like I was in love with the manager to get anything done.

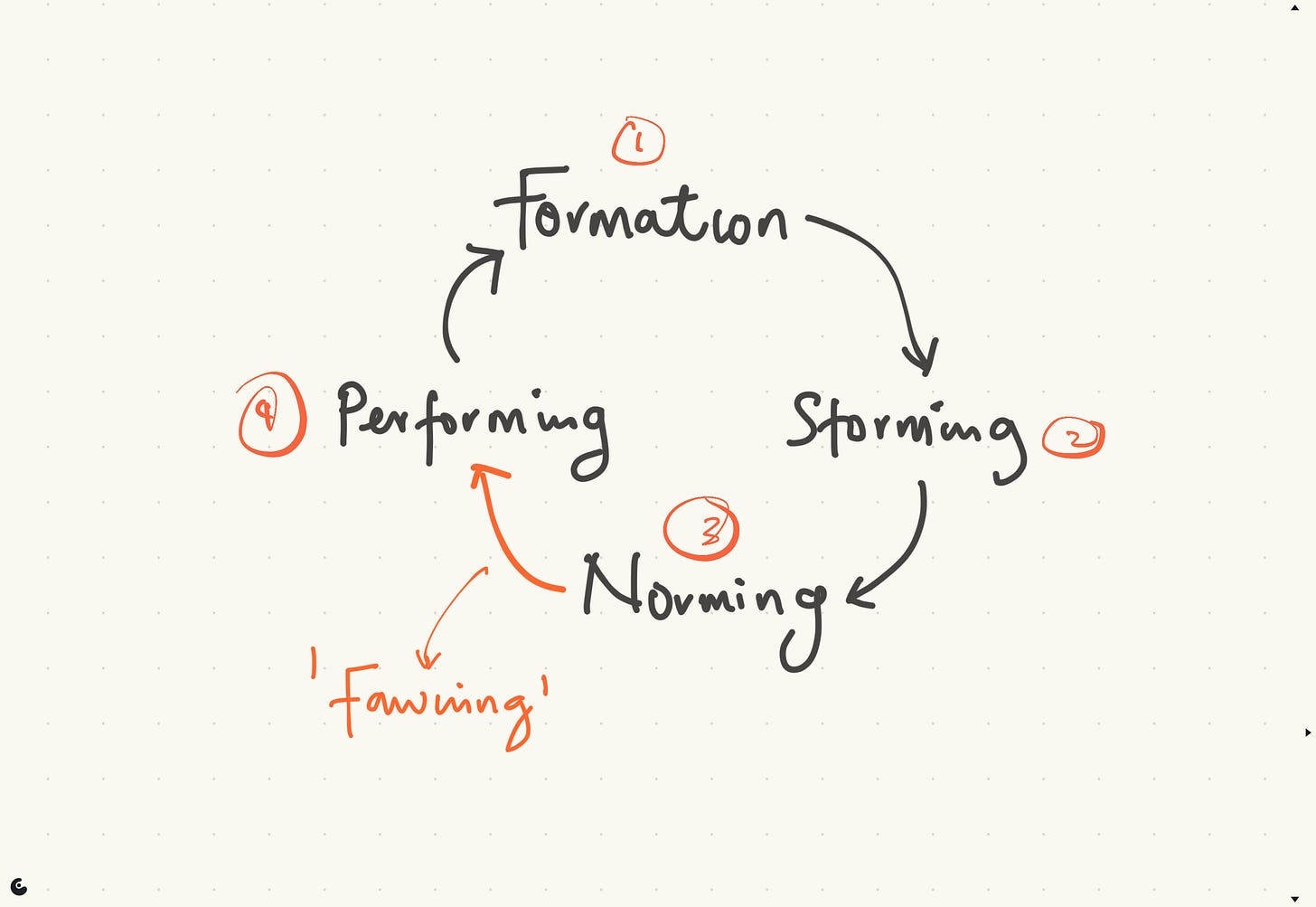

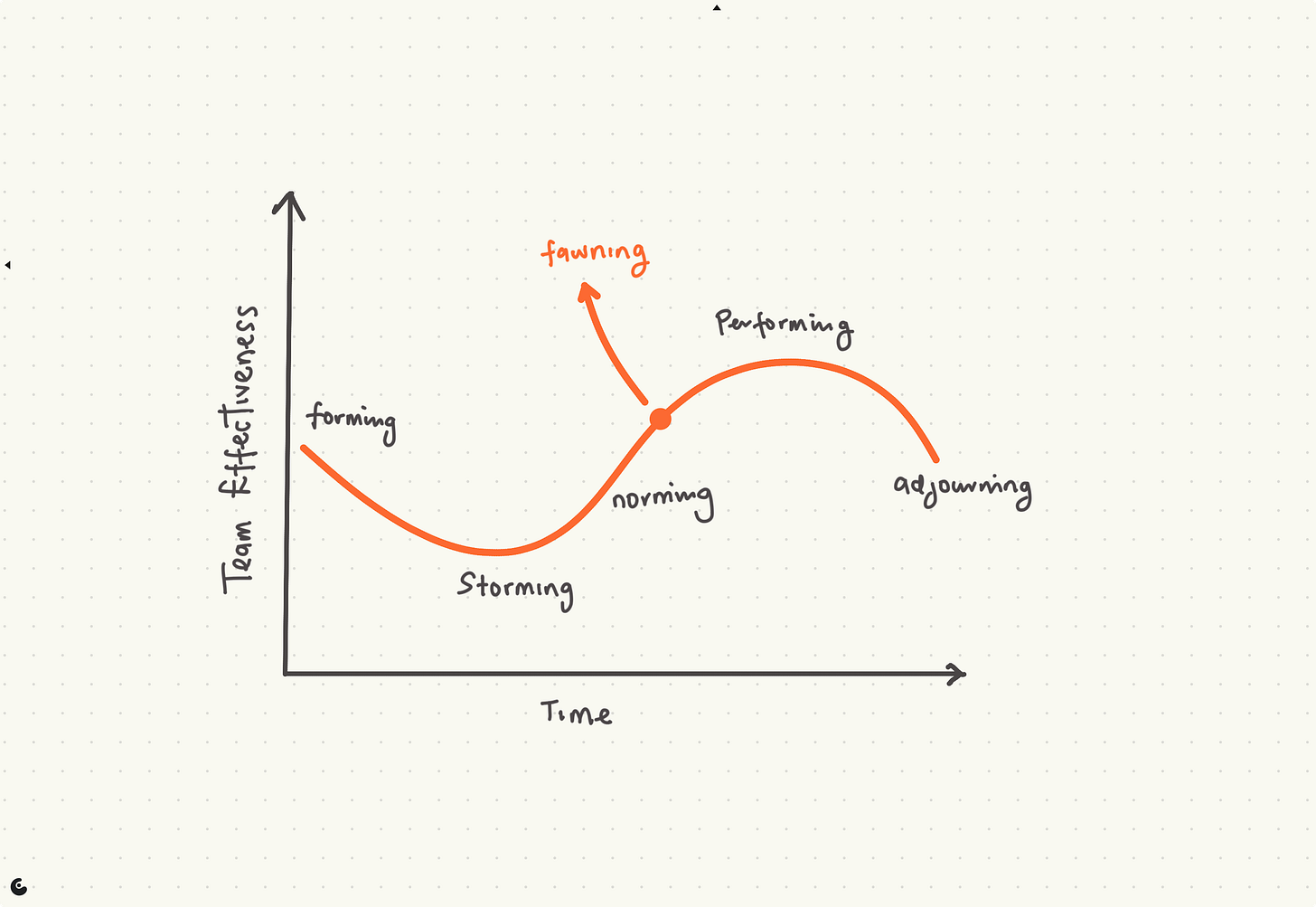

Fawning is a hidden, destructive behaviour that mimics “Norming” in the team formation process; when member of the team cannot get through the norming to performing stage, they implore a tactic called “Fawning”, a silent killer of true performance which trades competence for ego-stroking. If you’re not the type of person who enjoy politics, you might want to stay clear from this kind of environment, or ask yourself important questions when this is the only option available to you in an environment or even a situation. Fawning can often look like charismatic.

Fawning? What is it.

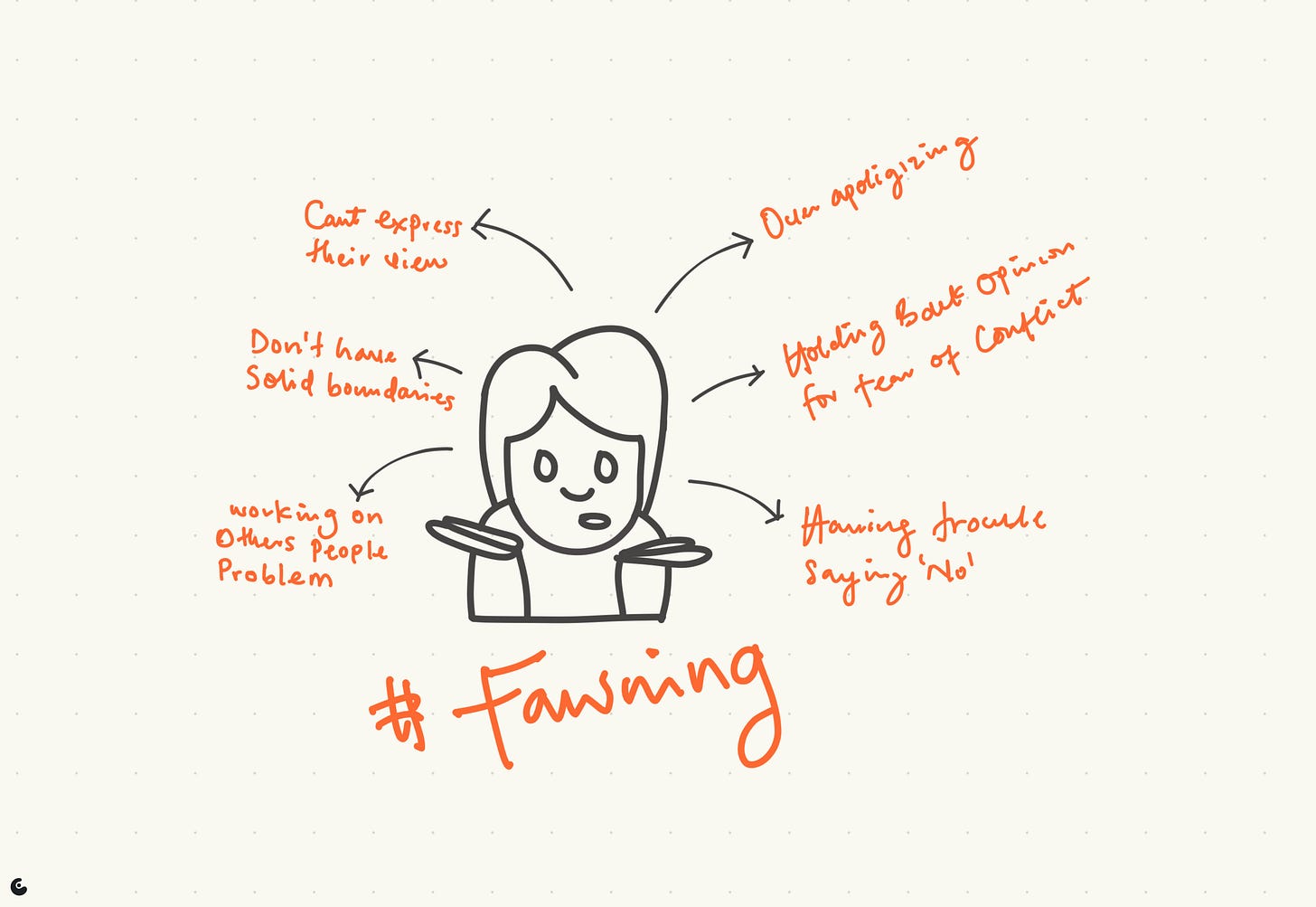

In a nutshell, I call it people pleasing. The difficulty of saying no, the fear of saying what you really feel, and denying your own needs, these are all signs of the fawn response. You neglects what you think is right, for what you think others want to hear. In a critical environment, this is detrimental to an healthy team formation.

The fawn is a trauma response, “a response to appease the threat by becoming more appealing to the threat,” according to, licensed psychotherapist Pete Walker, MA who is credited with coining the term fawning.”

The Illusion of “Culture Fit”

The common counter-argument is that social cohesion and “likability” are essential for a team to function. Proponents argue that high charisma and agreeableness; often labeled as “culture fit” lubricate the friction of early team formation, allowing the group to move quickly past the messy “Storming” phase.

However, this perspective confuses genuine social intelligence with fawning. Fawning is a trauma response or a manipulative tactic used to establish safety by appeasing power figures. In a professional setting, a fawner avoids necessary conflict and agrees with leadership regardless of the truth.

When we prioritise this “smoothness” over friction, we validate a false signal. A team member who challenges an idea is often labeled “difficult,” while the one who nods blindly is labeled a “good fit.” This creates a dangerous precedent where the appearance of harmony is valued more than the reality of the work. We begin to view participation, just showing up and blending in, as performance. But blending in is not the same as adding value.

Trap Between Norming & Performing

To understand the damage, we must look at the standard group development cycle: Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing. My critical insight is that there is a trap door between Norming and Performing this is the Fawning stage.

In a healthy “Norming” stage, a team establishes rules, respects differences, and agrees on how to work together. In the “Fawning” trap, the new employee bypasses the hard work of Norming. Instead of aligning on standards, they align on emotions. They mirror the leader’s desires to secure their position. Performing becomes performative.

This is a tactical deviation. The fawner cannot actually norm because they possess no authentic self within the group dynamic; they are merely a reflection of what the manager wants to see. Because they never truly “Norm”, which requires honesty, communicating personal constraints and boundary setting, they can never truly “Perform.” They get stuck in a loop of pleasing. The team feels united, but they are actually stalled, unable to reach the high-performance stage because one key cog is spinning freely, disconnected from the actual gears of the work.

The Managerial Ego

The persistence of fawning is rarely the fault of the employee alone; it is enabled by leaders with fragile egos.

Fawning is an addictive drug for a manager with low self-esteem. When a new hire tells you everything you want to hear, laughs at your jokes, and validates your genius, the dopamine hit is immediate. In my own experience, the founder fired me not because I couldn’t do the job, but because I didn’t provide that emotional supply. It forced me to set a rules of engagement with new clients, which stated that I will say things relating to the work, the founder may not entirely agree with to get the job done, and that they have to agree. You don’t have to agree with me every time, no appealing to feelings here, just hard fact based on actual evidence or strong rational.

The most critical failure in early team formation, is going from norming to performing, because of this phenomenal. Managers who lack the self-awareness to distinguish between a team member who respects them and a team member who is fawning over them. When a manager unconsciously selects for fawning, they are selecting for weakness. They build a team of “Yes Men” who make them feel safe, rather than a team of experts who make them successful, and say things that’s convenient sometimes. The moment it is time to perform, to face hard market realities, the fawner crumbles because their entire energy has been spent on relationship management rather than task execution.

How to spot, and mitigate fawning

Common signs to look for include: excessive agreement with all ideas in meetings, even contradictory ones. Consistently taking on extra work despite lack a of capacity, and constantly seeking reassurance on all work contributions.

While fawning behaviour can be attributed to an individual’s personal struggles, it could also be a sign of issues within the team dynamic, one of which is low psychological safety. A one to one consultation may mitigate this and provides clarity.

This dynamic is particularly common among design teams, where work is subjective and personal. If we do not actively mitigate the causes of fawning, we may stifle innovation. Design teams are vulnerable to fawning for these specific reasons, but each has a managerial solution:

1. Subjectivity traps

Design is often a matter of opinion, leading insecure designers to solve for the Creative Director’s mood rather than the user’s problem. We may need to move from opinion to evidence based approach. Managers must establish objective design principles and use user testing data, or factual artefacts as the arbiter of truth. When “good” is defined by data, the designer doesn’t need to fawn over the manager taste.

2. Trauma-based critiques

Designers with “critique trauma” from past toxic roles fawn to survive reviews, treating feedback as an attack. Separate the person from the work. Implement structured critique frameworks (remove “I like, I wish, I wonder, I feel”) and give feedback based on context, strictly on the output, ensuring the designer feels safe enough to disagree.

3. The know all leader

When a leader is a “Visionary Genius,” knows everything, the team learns that mimicry is the fastest path to approval. Implore speak last rules, withhold your opinion as the lead until the team has spoken. If the leader speaks first, they anchor the room; if they speak last, they invite honest exploration.

4. Imposter syndrome

Designers feeling like frauds will fawn to hide their perceived incompetence. Normalising vulnerability and admitting your own uncertainty or mistakes as a leader, may removes the need for the team to perform “perfection,” allowing them to focus on actual problem-solving.

5. Commitment deficit

Employees whose primary commitment lies elsewhere, overwhelmed, moonlighting, or using company time for external projects often leverage over-agreeableness as a shield against scrutiny, effectively buying the time and energy they are allocating to other pursuits. The goal is not to prohibit external activity entirely (which may be unrealistic or counterproductive to morale), but to eliminate the need for secrecy that breeds fawning and commitment deficits.

Conclusion

To summarise, we must stop confusing the silence of fawning with the stability of norming. Fawning is not a “soft skill”; it is a barrier to the final stage of team formation: Performing. My dismissal was a symptom of a leader who preferred the comfort of compliance over the friction of competence.

For managers and founders, the lesson is clear, If a new hire makes you feel consistently comfortable and validated in the first month, be skeptical. True performance requires the courage to disagree. Do not let your ego be the ceiling of your team’s potential.